David Rubinstein’s concert and recital career has brought the California-based pianist many times to Europe. He has recorded Bach, Beethoven, Sibelius, Satie and more, and in recent years has also found a digital platform for his work as both pianist and composer. With a growing series of YouTube video recordings – to which he has added, this autumn, a few of Grieg’s Lyric Pieces – Dr Sally Garden, the Society’s Honorary Director, talks to the pianist and composer about his work and artistic experiences.

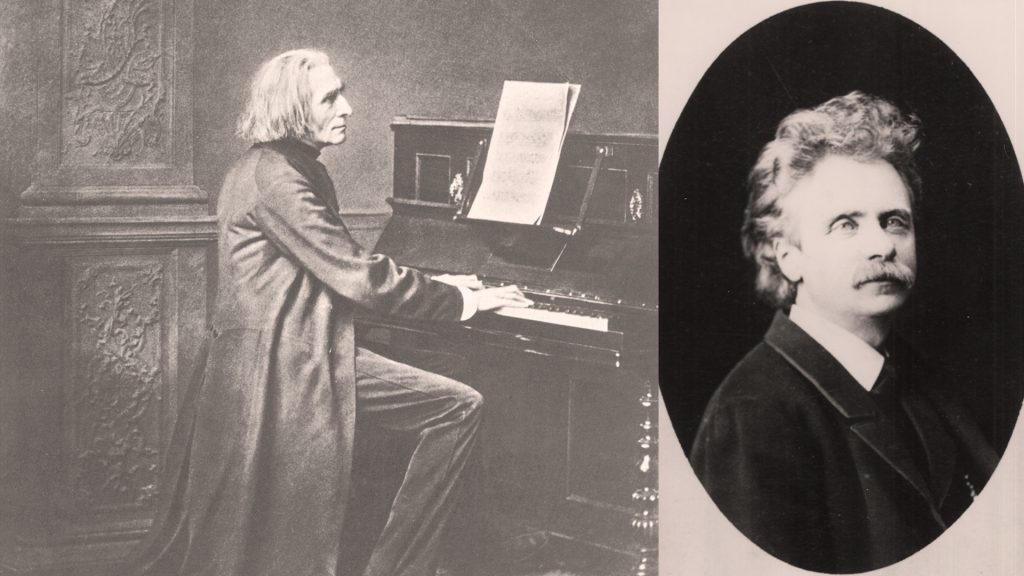

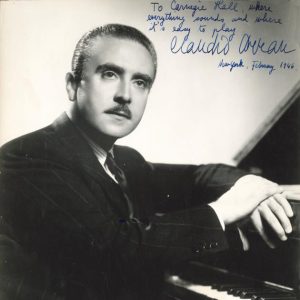

SG: One of the great influences in Edvard Grieg’s life was piano virtuoso and composer Franz Liszt, who gave great encouragement to the nervous young Norwegian when they met in Rome in 1870. One who gave you encouragement – in his way – was the great Chilean pianist, Claudio Arrau, with whom you studied for a time. Arrau, famously, was taught by a pupil of Liszt and was a master of Romantic piano repertoire. What was it like to study with Arrau and learn, in a way, from the spirit of Liszt?

DR: In 1980 I was fortunate enough to be introduced to Claudio Arrau via his agent Frieda Roth [Friede Rothe], who heard me at a private concert. I studied with him briefly in New York and Vermont. The lessons dealt mostly with freeing up my arms and upper body. Prior to this I tended to focus more on finger dexterity rather than the entire playing apparatus. I don’t remember what I played for him, possibly Beethoven and Chopin, but his approach gave me some of the tools needed to produce a bigger sound for those pieces that require it.

The Arrau ‘sound’, however, is not achievable by physical means alone, nor have I heard any other pianist who sounds remotely like Arrau. He was able to probe the depths of his chosen repertoire, especially in Brahms, Chopin and Liszt, where other pianists merely skate on the surface.

SG: Throughout your career you have taken a particular interest in rarer corners of the piano repertory – ‘modernist’ works such as Prokofiev’s challenging Piano Sonata No.4 and Busoni’s shimmering Elegy No.4 Turandots Frauengemach from the early twentieth century feature in your recordings. Grieg, though we don’t often think of him as a pioneer, stepped into the twentieth century too, with late works such as his monumental Slåtter [Norwegian Peasant Dances] Op72 and philosophical Stemninger [Moods] Op73 which, for Grieg, broke new ground. Thinking back, were you ever introduced to this ‘progressive’ side of Grieg during your piano studies?

DR: I was always familiar with Grieg’s music but it was not until my adult years that I took an active interest in his piano music. This was after hearing [Walter] Gieseking play some of the Lyric Pieces. The progressive aspect becomes evident as one studies and plays them. The turn of the 20th century turned out to be a turning point in harmony. Many composers including Grieg were moving away from traditional harmonies, each in his own way. But Grieg was not a wild experimenter. One can hear, for example, in Bell-Ringing [Klokkeklang] Op54n6 a bending of traditional harmony, but Grieg does it within his familiar territory. You can hear this in many of the Lyric Pieces but at the same time you feel a sense of satisfaction, not of experimentation.

I would also add that most of these Lyric Pieces are relatively easy to play, at least technically. How often do fine composers jeopardize the possibilities of performance by neglecting this consideration.

SG: As a composer, Edvard Grieg was inspired by landscape – Norwegian nature gave him many musical ideas. The Lyric Pieces you’ve recorded – Homeward [Hjemad], The Little Bird [Småfugl], The Brook [Bekken] and others – are all drawn from his experience of the environment. Might it be fair to say that your own compositions begin too, from external ideas? Not landscape, so much, as sounds, abstract ideas from the human world? Your Ping Pong Prelude, Piano Music for Two Fingers and several Circus-inspired works are witty and playful, but have serious purpose too. When did you first begin composing and what prompted you to start?

DR: Interesting questions, and I am glad to have time to think about them. Every composer works in his own way, and my way has changed over the years.

Aside from juvenile attempts at composing, I was involved with classical piano. I didn’t compose anything that I would consider worthwhile until my mid-30s, in conjunction with film. To explain: My classical piano playing career was put on pause when I moved to Los Angeles in 1985, without a grand piano, where I was mostly playing keyboards in film and television studios. I got the idea to submit my composing to production companies, so I created dozens of short pieces (‘demos’) – using a synthesizer – to emulate different moods. Later I realized that some of them were actually suitable as piano pieces (Filmic Preludes, Obsession). Gradually I composed more and more. But then I had the good fortune to inherit a Steinway. This changed things radically, and I re-focused on classical piano, and continued to compose.

You asked where my musical ideas come from. I can say that earlier they came from external sources. For example one composition was inspired by our fox terrier running around, so I called the piece Dog Tales. This little one seemed more like a clown than a dog. Later I changed the title and incorporated it into my collection entitled Circus Music.

More recently, I work with ideas – musical motifs – that pop into my head. This mostly happens in the middle of the night. I try to jot them down and later, during the day, I have a more careful look. In other words I never sit down at the piano and think ‘I am going to write some music’. Where these motifs ultimately come from is impossible to say, because after all, aren’t our subconscious thoughts stimulated by external objects and experiences? In any case these subconscious musical ideas are valuable to me because they come from a quiet time, or at least a time that is uncluttered by the many distractions of the day.

SG: The current pandemic has caused musicians to rethink how they reach and interact with audiences, as well as each other. It’s been a difficult time, but not impossible to be creative, as your portfolio of YouTube piano videos amply testify. Looking forward, what recording plans do you have for the future, and can we expect more Grieg?

DR: I hope to continue to record online videos and certainly more Grieg. Also, I’ll be looking out for some lesser-known Grieg works as well as having a fresh look at works which I have already played. My next live-audience concert (after the New Year) will feature Mozart, Schumann and some of my own compositions. Thank you again for giving me the opportunity to share some of my thoughts with you.

Author: Dr Sally LK Garden (Nov 2021)