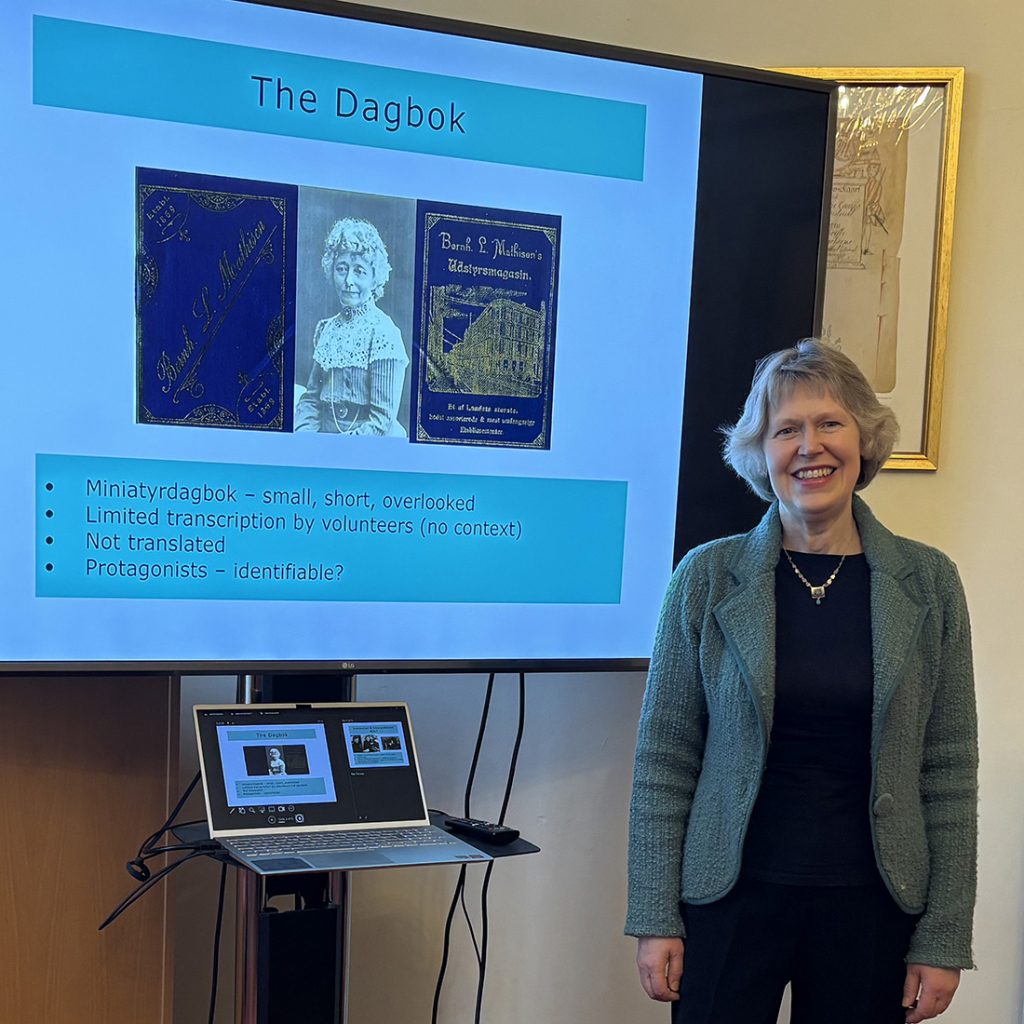

The little-known ‘dagbok’ or diary kept by singer and composer’s wife, Nina Grieg, was the topic of a talk and film preview given by Grieg Society of Scotland Honorary Director, Dr Sally Garden, in Edinburgh this spring. Society committee member, Eva Tyson, who attended the event hosted by the Norwegian Scottish Association, reflects on the significance of the diary as document of Nina’s experience, and the compelling sense of connection between researcher and historical subject her story has inspired.

The enthusiastic Norwegian Scottish Association (NSA) in Edinburgh invited our Honorary Director Dr Sally Garden to give a talk focussing on Nina Grieg, instead of her famous husband Edvard. This was deliberate, because as a Grieg scholar, Sally realised that Nina, although an artist in her own right, lived in the shadow of her famous husband.

Anguish and insecurity

There is an array of archive material relating to Edvard Grieg’s life of music, so Sally was delighted when she came across a diary of Nina’s in the special archives of Bergens Offentlige Bibliotek. This diary covered the year 1896-97, when Nina, aged 51, stayed in Vienna in connection with planned concerts by her husband. This was indeed a treasure trove, said Sally, as the diary gave a behind the scene account of Nina’s anxiety over Edvard’s poor health, leading to cancellations of the performances. This series of concerts had been scheduled in order to cement Grieg’s musical reputation in Vienna, the music centre of Europe. Things were not going to plan, as Grieg’s health did not improve and the anguish and insecurity Nina feels at this time, is palpable on so many pages.

However, Nina worked hard behind the scene to keep Grieg’s name at the forefront among the Viennese cognoscenti, which included composers, musicians and leading public figures. Sally mentioned here that Nina met Johannes Brahms, Johann Strauss the waltz king and potentially, Fritz Kreisler, who was both violinist and composer. Grieg’s impresario was also hard at work rearranging concert dates, with Nina having sleepless nights worrying about her husband’s recovery.

Vienna success and ‘a shadow on every page’

Sally’s talk gave us an insight not only into Nina’s psyche, but her dedication in both nursing her husband and promoting Grieg’s standing in Vienna, a city playing such a pivotal role for success, whether as composer or musician. The audience was relieved to hear that the diary during this year 1896-97 had a happy ending. Grieg became well enough and the concerts were a runaway success.

The situation Nina coped with during this stressful time, can be summed up I think by Eugene Ormandy, famous conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra. I don’t know if Ormandy was referring to a musical score, when he said ‘there is a shadow on every page’, but I feel it describes Nina Grieg’s diary to perfection.

The warm applause for Sally was well deserved and several questions from the floor followed. The vote of thanks was given by Chairman of NSA, Karl Norman Weibye.

Author : Eva Tyson (Committee Member, Grieg Society of Scotland) (April 2025, published June 2025)